Over the last several years, a general bi-partisan consensus had emerged in support of U.S. LNG exports. The Republican party has strongly advocated for exports and while staunch opposition persists among a small set of Democratic politicians, most followed the Obama administration’s position of offering tepid support—provided projects first complete a comprehensive permitting process.

Under the new Congress and Administration, that process is likely to come under serious review. Even in the final years of the Obama presidency, several pieces of legislation were proposed to expedite the approval process for U.S. LNG export projects, with a few coming very close to passage.

Most of the previously proposed legislation—as well as most of the early recommendations for the new Congress—were strictly centered on the part of the approval process covered by the Department of Energy (DOE). Under Section 3 of the Natural Gas Act, potential exporters are required to first gain approval from the DOE. Exports to countries with which the U.S. has a free trade agreement (FTA) are approved automatically, but the DOE has discretion over when and how to approve exports to countries without a free trade agreement (i.e., non-FTA countries).

Given that the bulk of global LNG demand comes from non-FTA countries, securing non-FTA approval from the DOE has long been considered absolutely critical for U.S. LNG project developers. Yet in practice, DOE non-FTA approval is a necessary but insufficient condition for project success.

Instead, it is the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) process that is and always has been a much stronger determinant of the pace and ultimate success of project development. FERC is obligated by the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) to issue a full Environmental Assessment (EA) or Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for any proposed LNG project that has submitted a complete application. Preparing the application and completing the full review process is time consuming and expensive. Most applicants, after submitting their application, have waited nearly two years for the Commission to issue approval. Costs, according to developers, can easily approach $100 million.

Notably, as a result of guidance from the Obama administration established in 2014, the DOE can issue a non-FTA export permit for a project only after FERC completes its full environmental approval process.

Yet, despite the primacy of the FERC process, DOE non-FTA approval has always received more legislative attention. Nearly all of the bills proposed in Congress have simply called for DOE to be required to issue a non-FTA decision within 30-45 days of a final FERC decision.

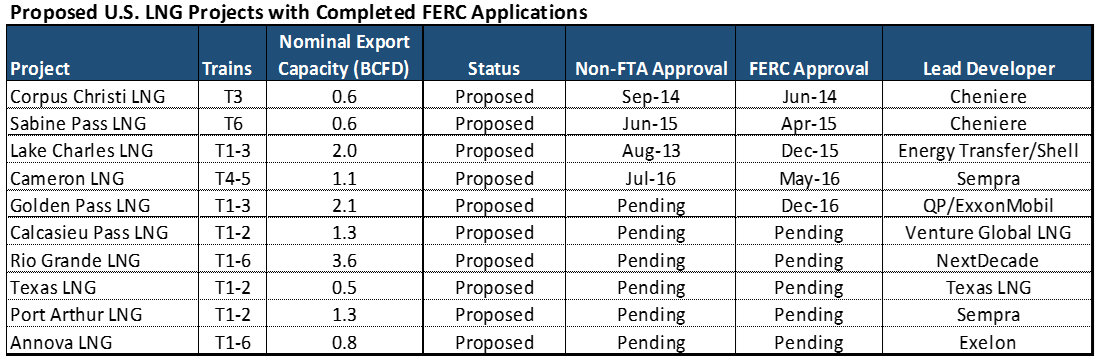

Such modifications to the existing DOE process are largely a solution looking for a problem. They would limit some downside risk for project developers and potential buyers looking to sign offtake agreements, but Obama’s DOE never denied a non-FTA permit after a project completed the FERC process. It typically issued non-FTA approval within a few months of FERC approval (as seen in the table below).

Thus, unless the FERC process is meaningfully modified, the overall developmental timeline for U.S. LNG projects would be largely unchanged. Regardless, Republicans are likely to re-introduce similar DOE-focused language in future sessions, meaning some version of the legislation is likely to ultimately be codified.

For its part, the new administration has not spoken explicitly about LNG exports, but it would surely support such measures. It has continuously advocated for energy infrastructure development, including an executive order directly targeting pipeline development. Rick Perry, the soon-to-be confirmed pick for Energy Secretary, could accelerate the DOE approval process even without a direct mandate from Congress—though legislation would of course be more permanent.

A separate issue potentially impacting U.S. LNG development is the new administration’s trade policy, specifically its opposition to international trade deals such as the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). There has been some concern in the industry that as a result of officially exiting the TPP, the U.S. may have newfound difficulty exporting LNG to the 11 other nations in the partnership.

This concern is unwarranted for two clear reasons. First, the TPP only included a few LNG importers. The most notable is Japan—by far the largest LNG importer in the world—but excluded growing importers, such as China and India, as well as all European countries. Even if other TPP participants, in some effort to punish the U.S. for exiting TPP, refused to buy additional LNG, the impact would be entirely negligible.

Second, the above hypothetical is extremely unlikely, as exiting TPP merely returns the dynamic to the status quo. Under that system, Japan had no qualms establishing itself as one of the largest buyers of U.S. LNG, signing sizeable long-term contracts with several projects soon to come online. Buyers from Japan, other TPP nations and any other country without an FTA with the U.S. will still require specific DOE approval, but as described earlier, non-FTA approval is all-but guaranteed—especially under the new administration.

Thus, U.S. LNG developers have no true regulatory obstacles to securing buyers from a wide range of countries without an FTA, regardless of the status of TPP.