As of late-April, Sabine Pass has exported more than 100 LNG cargoes to 17 different countries. Regionally, the shipments have been split almost equally between South American, Asian and Middle Eastern markets, fluctuating based on seasonal demand. Yet somewhat unexpectedly, the single largest importer of U.S. LNG is the country that would otherwise seem to need it the least: Mexico.

Mexico has long been an obvious destination for cheap U.S. gas. Total Mexican gas demand has been rising rapidly, primarily driven by increasing power demand. Demand growth has been especially strong during the hot summer months, the result of increased adoption of air conditioning. Industrial demand has been surging, as well, especially in the more-developed eastern part of the country.

Yet it was widely, and understandably, assumed that U.S. gas exports to Mexico would be via pipeline, not LNG. Given the considerable costs associated with liquefaction, shipping and regasification, pipeline gas is an inherently cheaper option for neighboring countries.

To be sure, there has been no shortage of new pipeline capacity being added to direct U.S. gas across the border to Mexico. Several large projects have already been completed, pushing pipeline exports to average 3.7 BCFD in 2016, up from only 1.8 BCFD in 2013. Pipeline exports have surged even higher through Q1 2017, averaging 3.9 BCFD, and are expected to top 4.8 BCFD by the end of the year.

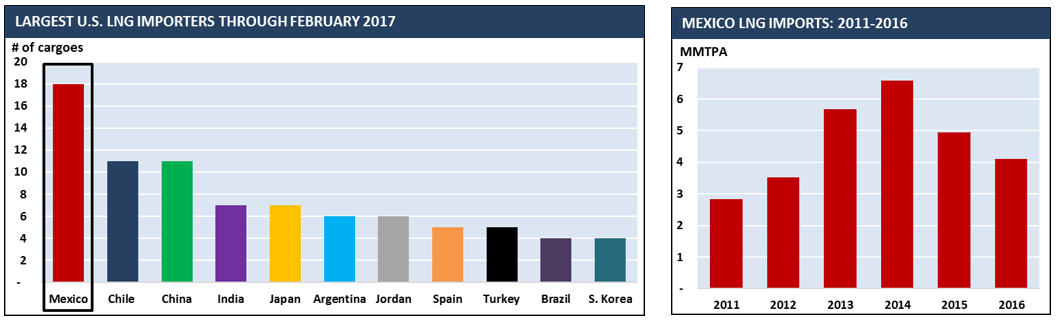

Yet at the same time, Mexico has also established itself as the largest importer of U.S. LNG. The country imported nine cargoes in 2016, seven of which were imported in November and December. Mexico has already brought in an additional nine cargoes just through February 2017 (the latest date for which data is available).

The combined 18 cargoes dwarfs that of the second largest importers of U.S. LNG, China and Chile, which have purchased only 11 cargoes each. Pipeline imports still far outweigh LNG imports, but the frequency of the shipments to Mexico have been somewhat unexpected, the result of a confluence of unrelated events.

Most notably, a contract dispute between Mexico and Peru LNG has opened the door to U.S. LNG. The bulk of the U.S. cargoes have been directed to the Manzanillo import terminal on the country’s Pacific coast. Historically, the 3.8 MMTPA terminal has been supplied almost exclusively by the Peru LNG project, based on a long-term contract dating back to the late-2000’s.

The contract between Mexico’s state-run utility, CFE, and Shell, the offtaker from Peru LNG, is linked to Henry Hub, but was signed under very different pricing dynamics. U.S. gas prices at the time were approaching $10—roughly in line with global LNG prices—and the U.S itself seemed destined to become one of the world’s largest LNG importers.

The subsequent divergence between falling Henry Hub prices and much higher global LNG prices was a decidedly negative outcome for Peru, which was effectively forced to sell the bulk of its LNG to Mexico well below market prices.

As a result, the Peruvian government has long pressured CFE to renegotiate the contract. CFE has always refused to do so but in October, Peru LNG shipments to Mexico suddenly came to a halt. Since then, only one cargo has been delivered, leading some to speculate that the contract had finally been renegotiated or cancelled outright. It is also possible that Shell is simply paying a penalty to send Peruvian cargoes to more lucrative markets, while directing many of its U.S. cargoes (Shell is the primary offtaker from Sabine Pass) to Mexico.

The Peru LNG contract dispute is not the only factor pushing U.S. LNG into Mexico. For the last few months, pipeline exports from the U.S. have held largely flat due to maintenance on the Agua Dulce compressor station and the 2.1 BCFD NET Mexico cross border pipeline. Those issues will be resolved shortly, but three other pipelines within Mexico have recently announced delays, as well. All three are designed to ship gas into the east-central region of the country, and their delay has driven a recent surge of LNG into the Atlantic coast import terminal, Altamira, which had otherwise been expected to be highly underutilized (it had last received a cargo in August).

Finally, overall LNG demand in Mexico has been bolstered by a rapid decline in domestic gas production. PEMEX, which until recently held a monopoly on upstream oil and gas production in Mexico, has been unable to reverse the long-term decline of production from existing fields, which has fallen more than 20% over the past several years.

Mexico’s 2013 Energy Reforms were supposed to encourage outside investment and boost output, but broader energy market conditions have reduced investment interest for the time being. Gas production in early 2017 has been so low that CFE has increasingly turned to fuel oil and diesel for power generation, while simultaneously releasing tenders for several additional LNG cargoes through April and May.

Combined, these factors have produced a gas shortage that is likely to keep U.S. LNG flowing to Mexico through much of the summer, with total 2017 LNG demand likely to largely match that of 2016—though still well below the 2014 peak.

The longer-term outlook, however, is for LNG demand in Mexico to decline as the current tranche of pipeline projects is completed. Beyond 2018, LNG imports are likely to be limited to summer purchases for system balancing. This means the U.S. will have to find a new favorite customer for its LNG, but with global demand rising rapidly, it should have little difficulty doing so.