California finding it difficult to get past natural gas

In late 2019, Southern California Edison released “Pathway 2045”, its report on how the utility will meet the state’s aggressive carbon reduction mandates. Just over a year earlier, then-Governor Gavin Jerry Brown (D) signed into law S.B. 100, which accelerated the state’s existing renewable portfolio standard to 60% by 2030 and established a goal of 100% by 2045. The other interim targets and compliance periods were also accelerated. At the time, it was the most aggressive RPS in the country[1] and would require the state to replace nearly all its gas-fired generation with carbon-free alternatives. Currently, one-third of California’s power demand is met with natural gas while another one-third is imported from neighboring states[2]. Under the RPS, state utilities must source at least 33% of their retail sales from renewables in 2020. Exhibit 1 contains a chart showing the annual RPS procurement requirements as defined by the California Public Utility Commission (CPUC).

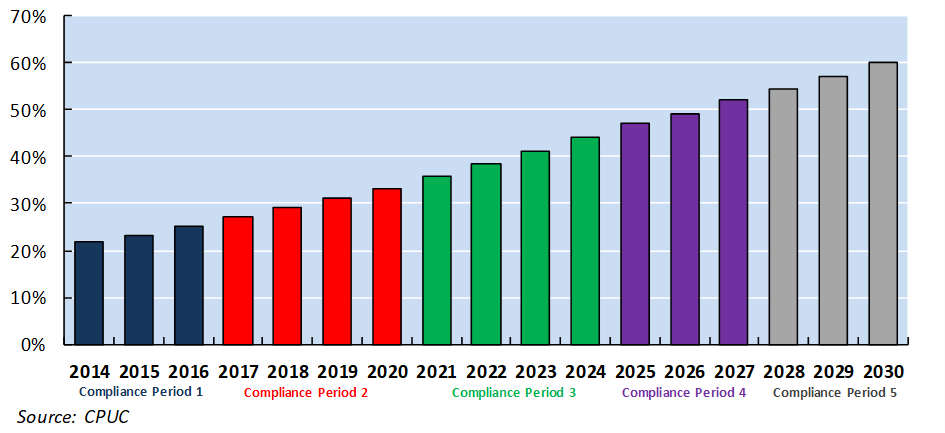

Exhibit 1: RPS procurement requirements by compliance period

The CPUC’s 2019 annual RPS compliance report indicates that roughly 110,000 GWh of RPS-eligible generation will be required by 2030. The report also highlights that the three large investor-owned utilities in the state – Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric – all exceeded their required RPS shares in 2018. CPUC expects them to continue surpassing their requirements through at least 2025 based on resources that are already under contract.

RPS to drive unprecedented pace of renewable development

In its report, SoCal Edison projects that at least 80 GW of utility-scale renewable capacity and at least 30 GW of utility-scale battery storage capacity will be required by 2045 to economically meet the state’s ambitious decarbonization goals. While this is a daunting number, consider the state’s recent track record of renewable development. Since 2013, California has built an average of 1,500 MW of utility-scale solar PV capacity per year, nearly three times the rate of North Carolina, the next-most prolific state. Wind development, however, has trailed that of the wind-rich Central and Midwestern states, averaging just 150 MW per year since 2013.

To supplement the renewable generation inside the state, utilities in California contract with or purchase renewable energy credits (REC) from out-of-state generators. Based on the IOUs’ compliance reports, roughly 25% of their RECs will come from out of state resources during Compliance Period 3, up slightly from Compliance Period 2.

Natural gas continues to find a role in California

According to SoCal Edison, natural gas will make up 6% of annual power generation in 2045, with roughly 10,000 MW of gas-fired capacity remaining online to be primarily utilized during high load or low renewable periods. The utility found that removing natural gas entirely from the grid would “significantly increase resource costs” to the tune of 40% and notes that the remaining gas plants are key to maintaining reliability and affordability.

Already, utilities and the California ISO are finding it difficult to reduce their reliance on gas. Four gas-fired plants comprising 3,700 MW in Southern California were required by the State Water Resource Control Board to shut down by the end of 2020 in order to comply with the state’s once-through cooling regulations, but received extensions after an analysis showed that California may face power shortages beginning in the summer of 2021. Steve Berberich, CAISO’s CEO, raised concerns after a June 2019 heatwave that the grid will struggle to meet loads around 50,000 MW – similar to recent summer peaks – amid continued plant retirements and growth in intermittent renewables. SoCal Edison’s Pathway 2045 report appears to acknowledge this fact and part of its solution lies in battery storage, which it says can provide similar flexibility as natural gas plants.

Stakeholders have also championed hydrogen and renewable natural gas as potential options to help smooth the grid transition and fuel baseload resources in a carbon-neutral world. These technologies are not yet commercially available.

New York’s plan appears to be stricter despite in-city challenges

New York, which passed the most aggressive RPS in the country last summer, also relies heavily on natural gas for power generation. The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA) expanded the Clean Energy Standard to 70% by 2030, and 100% renewable by 2040. Currently, all generating capacity operating in the congested New York City region is gas- or oil-fired. These plants are critical to maintaining reliability given the limited transmission and the fact that the city accounts for one-third of the New York ISO’s annual and peak demand. Two new gas-fired combined cycle plants were recently built to replace Entergy’s retiring 2,100-MW Indian Point nuclear plant just north of New York City.

The state’s projections indicate that just 10% of generation by 2030 will be gas- or oil-fired, and that number falls close to zero by 2040 thanks to the CLCPA, though there are few details about how load will be met in densely-populated New York City or during times of low renewable generation. More recently, the New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) proposed creating a fourth tier of RECs specifically for renewable projects that can deliver power into New York City. Several of the state’s in-development offshore wind projects are slated to deliver power into the city.

EVA continues to model and assess renewable transitions in the U.S. energy sector. For more information or to inquire about an engagement, please contact Rob DiDona at [email protected].

[1] New York in June 2019 passed a Renewable Energy Standard requiring 100% renewables by 2040.

[2] These shares vary by month and year.